On Visionary Founders Part 1: Would Jay Gatsby be Investable?

From a young age, my two great passions were literature and entrepreneurship. At various times, when I was asked “What do you want to do when you grow up?” I said I wanted to write a novel, start a company, or, in moments of greater confidence, both.

Today, I’m the co-founder of PodPlay Technologies and my wife’s debut novel will be published in January 2025 (1). So my younger self wasn’t too far off the mark.

While many think of starting a business as “non-fiction” and literature as “fiction”, I think the lines are much more blurred. Both are about creating something out of nothing–taking an idea and shaping it into a reality that connects with people. And if you think startups are risky and fraught with uncertainty, try writing a debut novel on spec!

I think literature has much to tell us about the path startups must take to go from zero to one–from a compelling vision to a reality that connects with customers.

One book I return to often in thinking about startups and founders is The Great Gatsby. There is something about Jay Gatsby’s romantic optimism that mapped into the conception of the visionary founder I had in my mid-twenties. Gatsby’s uncompromising vision and charisma seemed like key characteristics of a visionary founder. And I’m willing to bet that The Great Gatsby remains very popular amongst young, ambitious founders.

As a 50-year old veteran of multiple startups, I still see in Gatsby hints of the visionary, but I am also acutely aware that my younger self managed to look past the fact that Jay Gatsby ends up dead in the bottom of a pool.

In this blog (Part 1 of 2), I will examine the archetype of the visionary founder through the lens of The Great Gatsby and make the case that vision divorced from reality is a tragic flaw that will land a startup in the bottom of the proverbial pool. I present Sam Bankman-Fried as a cautionary example of a modern day Gatsby–a visionary founder who failed to turn vision into reality.

In Part 2, we will revisit the archetype of the visionary founder through the lens of two companies that have made a dent in the universe: Apple and Stripe. These two companies have turned powerful visions into even more powerful realities. I will argue that a relentless focus on craft and quality by each of these company’s founders is the key to turning an ambitious vision into a reality.

The Visionary Founder Archetype

A popular archetype for Venture Capitalists and other early stage investors is the visionary founder.

Elad Gil, is the author of The High Growth Handbook, and someone who has come into contact with his fair share of visionaries as an investor in AirBnB, Instacart, Notion, Square, Stripe and others. He describes visionaries as “people with a singular vision for what they want to accomplish. They view their product or company as the vehicle by which they can fulfill a messianic mission to change the world.”

The visionary has an uncompromising, fundamentally optimistic vision of a future they want to bring about. They attract others to the project based on force of personality and vision. They are maniacal about the product or service, and unwilling to relent in their pursuit of the vision, inspiring both love and hate.

This description fits Jeff Bezos and Steve Jobs.

It also describes Jay Gatsby and Sam Bankman-Fried.

Jay Gatsby as Visionary Founder

So how does Jay Gatsby map into the archetype?

✅ Optimism and belief

Gatsby allows others to believe anything is possible. Fitzgerald writes, “there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away.” Gatsby has a fundamentally optimistic view of the future, that Fitzgerald describes as “an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again.”

✅ Uncompromising vision

Gatsby’s uncompromising vision is of his future with Daisy Buchanan, a vision famously evoked by the image of the green light on the end of Daisy’s dock. Fitzgerald writes, “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.” He likened Gatsby’s vision to what Dutch sailors must have felt upon arriving in the New World: “the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent….face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

✅ Charismatic / Messianic

Gatsby is charismatic and inspires both love and hate. Fitzgerald’s description of Gatsby’s smile captures the essence of charisma and its power to inspire: “It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced–or seemed to face–the whole external world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey.”

On these filters, a young Jay Gatsby (before he met Meyer Wolfsheim) might have been a decent bet for venture capitalists. But he failed to turn a compelling vision into a lasting reality. With hindsight, what went wrong?

Delusional Optimism as Gatsby’s Tragic Flaw

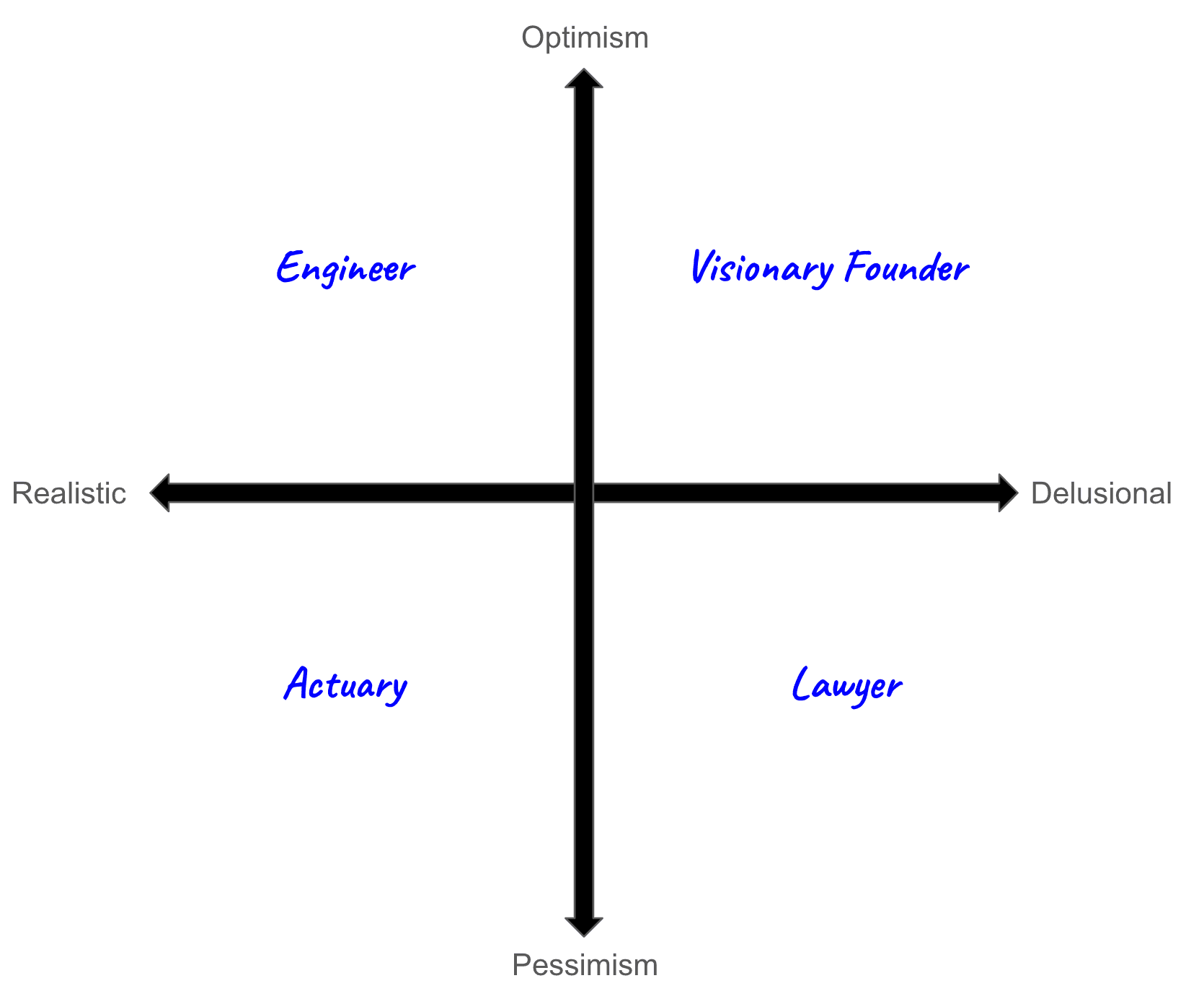

We can loosely map people into a 2x2 matrix with the vertical axis running from pessimism to optimism and the horizontal axis running from realistic to delusional. The pessimistic half of the matrix is where you are likely to find people working in law, compliance, and insurance. Mapping into the optimistic half of the matrix is table stakes for startup founders. The odds are overwhelmingly against success, so a healthy measure of optimism is required to even get started. But what is more likely to produce venture scale outcomes: delusional or realistic optimism?

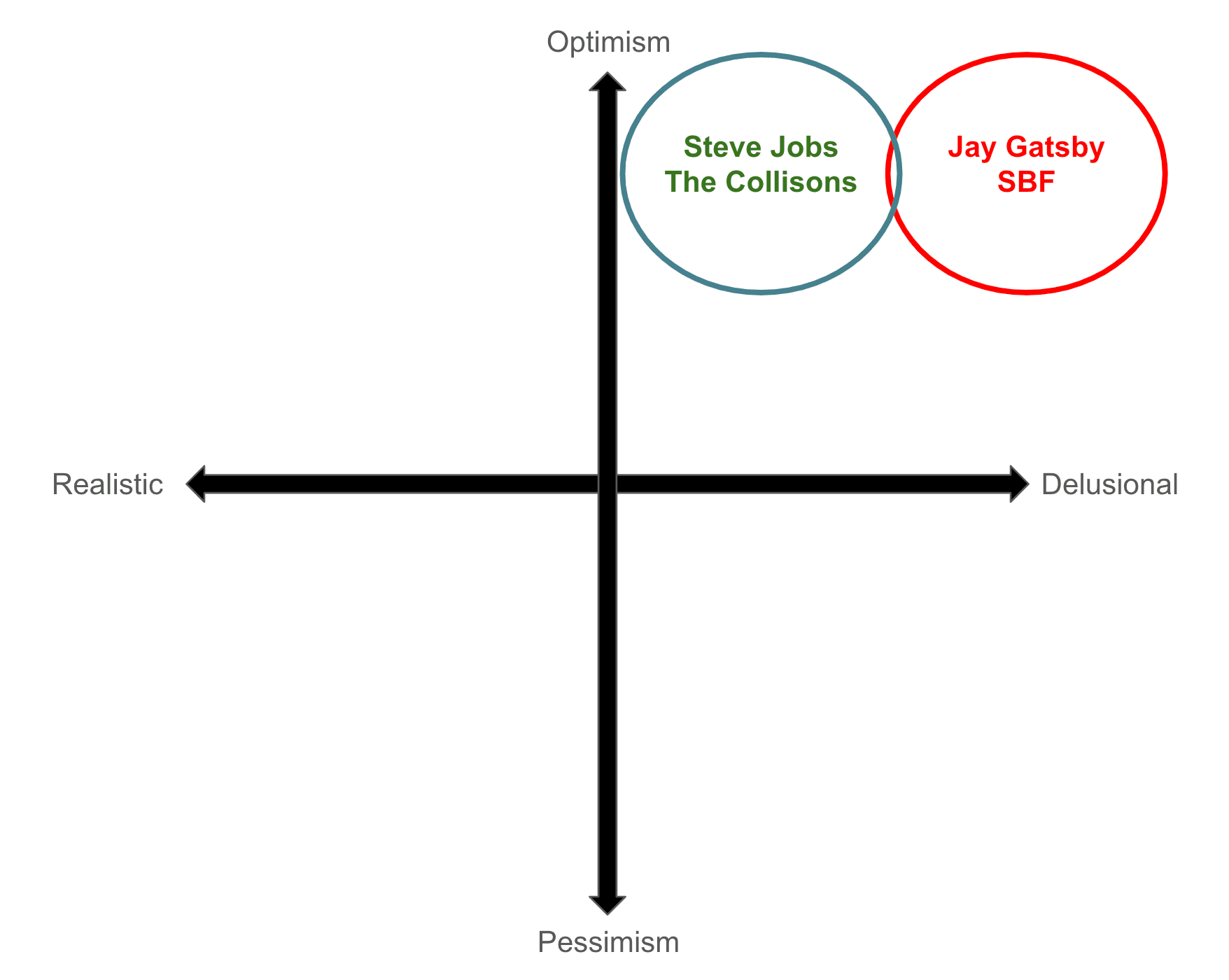

Jay Gatsby was a delusional optimist. Blind faith in his vision, in the face of evidence to the contrary, was his tragic flaw. The target for visionary founders ought to be rating high on optimism and more balanced over time on the scale of realistic to delusional. True visionaries will always lean a little delusional. To go from

there is a certain amount of belief-without-evidence required in order to just get started. The genius of the visionary is being able to describe a future state of the world in a way that compels investors and team members to join a mission in the face of a high degree of uncertainty about the outcome. But as a venture progresses, vision meets inevitable obstacles. Craft, hard work, and execution are what turn a vision into a reality. And it is how the visionary chooses to address those obstacles that lead them to succeed, or alternatively, end up at the bottom of the proverbial pool.

If we go back to our matrix, I think it is instructive to map visionary founders, who produced huge successes and failures, into it.

SBF as Modern Day Gatsby

The closest thing we have seen to a modern day Gatsby is Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF). While Gatsby was known for his trendy peacocking style, SBF created a brand of his own: signature fro, cargo shorts, T-shirt, and New Balance sneakers (2). Like Gatsby, he came out of nowhere and inspired wild rumors. As Michael Lewis writes, “Inside of three years, it appeared, Sam Bankman-Fried had created a business so valuable that his share of it implied that he was now the richest person in the world under the age of thirty.”

Photo: Twitter / Dan Keeler

SBF inspired not just rumors, but investment. One venture capitalist told Lewis that Sam had a real shot at being the world’s first trillionaire. In about twelve months during 2020 and 2021, FTX sold roughly 6 percent of the company for $2.3 billion to approximately one hundred fifty different investment firms across four rounds of fundraising. All of this investment came without any of the usual investor protections. Lewis writes that, “All of them caved to Sam’s refusal to give them a seat on the board (he had no board) or any other form of control over the business.”

Venture capitalists saw SBF as a visionary founder. Why?

✅ Optimism and belief

SBF presented FTX as an innovative new kind of vehicle for generating profits which he then planned to channel into solving some of the world’s biggest problems. “For him to build the business he was describing, it would be the largest global crypto exchange and then go beyond that—to become the largest global financial institution,” said one venture capitalist. Crypto was born out of the ashes of the global financial crisis with a view towards remaking the financial system. And while the original ideas were based on mistrust of existing institutions, by the time SBF founded FTX, crypto had become as much a vehicle for utopian visions of the financial future as response to a dystopian financial event.

✅ Uncompromising vision

SBF was the most visible public proponent of the philosophical and social movement known as Effective Altruism (EA). The core idea of EA involves impartially calculating benefits and prioritizing causes to provide the greatest good. All actions are seen through the lens of expected value. The most effective way for SBF to pursue his altruistic goals was to create a money making machine. He could save more lives by making money than by becoming a doctor. In 2021, when Lewis asked SBF how much money he would require to sell FTX, SBF’s answer was one hundred and fifty billion dollars, though “he had use for infinity dollars.” One hundred fifty billion dollars was what SBF calculated was needed to address one of the major problems facing humanity. As Lewis wrote, “he planned to use his money to address the biggest existential risks to life on Earth: nuclear war, pandemics far more deadly than Covid, artificial intelligence that turned on mankind and wiped us out, and so on.”

✅ Charismatic / Messianic

SBF managed to transmute oddness into a kind of charisma that engendered intense belief. Lewis wrote that, “Sam was odd on TV, but he was also odd in real life. In real life people who encountered him often thought he was the most interesting person they’d ever met.” One venture capitalist said that, “Sam didn’t resemble most of the entrepreneurs he’d dealt with. He’s not a showman. He’s not a salesman. He’s got a nonconventional way of thinking about building his organization. Everything is probabilities, and he’d pull these probabilities out of thin air. And then he’d change them. He’s sleeping on a beanbag. He’s doing all of this by himself. And he doesn’t seem particularly interested in our opinion on anything. Which is fine. But we were like, he’s an unusual person.”

With the benefit of hindsight, the collective estimation of SBF proved an enormous and costly miscalculation. Why did so many people not see it coming? They were blinded by a narrative and a cult of personality. As one employee of FTX said, “His oddness mixed with just how smart he was allowed you to wave away a lot of the concerns. The question of why just goes away.”

The world over-indexed to vision and personality and ignored that SBF’s vision was divorced from reality. SBF, like Gatsby, had an inability to accept facts as truth when reality came into conflict with his vision.

Vision alone is not enough. For grand visions to become realities, they must be paired with hard work, execution, and a relentless focus on craft and quality.

In Part 2 of this series, we will examine two examples of companies with visionary leadership that have been able to turn powerful visions into even more powerful realities: Apple and Stripe.

Footnotes

(1) Readers who find this blog more interesting than weird will enjoy my wife Sash Bischoff’s debut novel Sweet Fury, which is, at once, a lyrical literary thriller and in conversation with the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Don’t trust the opinion of a proud husband? Here is what Joyce Carol Oates says: “Sweet Fury is a wildly imaginative, very dark romance of a kind that would have shocked F. Scott Fitzgerald, that icon of the Roaring Twenties. Filled with surprises, unpredictable in its denouement, this audacious first novel is a subversive and highly entertaining exploration of the theme of ‘romance’ itself.”

(2) All quotes in this section are from Michael Lewis’ Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon

*Originally published by Ben Borton, Aug 26th, 2024. The article is on PodPlay's blog.